An ancient Judaean group called ‘Essenes’ has fascinated the West for nearly 2,000 years, ever since three independent first-century authors—Philo of Alexandria, Pliny the Elder, and Flavius Josephus—portrayed them in various awestruck accounts. From about 1950, most specialists in Judaean history identified the scrolls found near the site of Qumran, on the northwest edge of the Dead Sea, which had just come to light, as Essene products. Since neither the site nor the scrolls identify themselves as Essene, none of the portraits of the Essenes mentions any such site, and the scrolls’ contents differ from the Essene descriptions at various points, this identification was not self-evident. It was based on a combination of circumstantial evidence, a bold new reading of one Essene portrait and adjustments to the others, and a process of elimination that suited the early 1950s, but would not be possible today. (‘There were Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes. If they don’t look like the first two, they must be the third.’)

With the gradual unravelling of those assumptions in the past generation, closer attention to each of the texts, and a natural process of ever-closer questioning, many scholars have come to doubt or qualify the proposed Qumran-Essene bond. Meanwhile, others have forged new connections: between Qumran and/or the Essenes and John the Baptist, Jesus, or early Christians. How should the non-specialist judge all these moving parts or balls being juggled in the air?

This blogpost cannot resolve all, or any, of the questions that might interest each reader. In all such matters—and there are many in the fields of ancient Judaism and Christianity—I take refuge in historical method. When people spot parallels between two things, it is awfully tempting to forget about method, imagine connections, and then bend the evidence to suit the picture. Subscribers to testimonia.pl will know that last summer I published a two-part essay on historical method. The present blogpost is my effort to apply it to the problem of the Essenes. Let me stress that I do not see this as the last word on any subject covered here. It is more of a way of approaching the subject, for those who are willing.

Reminder: Historical Method

The core of the method (by which I mean both ‘rationale’ and the procedures that follow from it) is basically this. Granted that human life in the past, like life in the present, was a chaos of interactions that did not occur as neat stories or declare their own meaning—that is why every year sees new and innovative studies even of the world wars, but also of first-century issues—history was born from the realisation that we can only claim any understanding of things we methodically investigate. The Greek word historia meant, first of all, investigation or inquiry. At bottom, a historian is a detective travelling back in time, following some such procedure as this:

- Formulate a problem to investigate. The past does not speak to us, and we cannot grasp all of life, in our own time and certainly not in any previous generation. We can only get somewhere by conducting methodical investigations into particular problems.

- Identify the most relevant evidence. A detective informed of a body with a knife in the back is likely to be handed the problem: Who killed John Doe? Even if John Doe had traffic violations or was found to have used illegal drugs, the detective’s job is not write a biography or bring charges, but to solve the problem at hand. To do so, the detective will call for forensic study of the body, knife, and immediate surroundings (physical evidence) and also identify witnesses, of the incident itself or the environment at the time it occurred, to give accounts of what they saw. Likewise, the historian needs to understand both material remains, where they are available, and any surviving accounts of the event or object being investigated. Of course, the scope of evidence may well grow during the investigation, but we begin with and prioritise evidence directly bearing on our object.

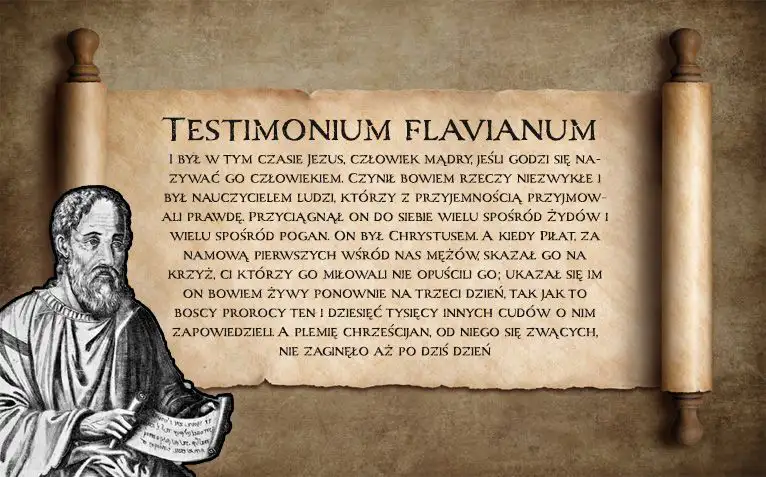

- Interpret the evidence. Before going farther, the investigator must understand each piece of evidence for what it is. As R. G. Collingwood pointed out (Idea of History), if someone declares ‘I killed John Doe’, the competent detective may not say: ‘OK, problem solved!’ People sometimes confess to crimes they did not commit, from a psychological disorder, a wish to protect someone, or coercion by powerful criminals. The must first ask why this person is saying this. Who is this person and how is he or she involved? In a similar way, the historian cannot use a coin, inscription, or text to help solve the problem without some understanding of the thing being used, whether a symbol on a coin from King Herod’s reign or Pilate’s governorship, or a statement in Josephus’ narrative. Bracketing the problem I’m investigating for a moment, what does this thing I see in front of me mean, in its own contexts? Why was it created? If I misunderstand the coin image or the sentence in Josephus, I’m going to build my historical picture of Herod, Pilate, or Josephus’ Essenes on a faulty foundation.

- Hypothesise possible solutions to the problem that would explain the evidence. Every part of the historical process (as of scientific method) requires imagination. Already when we think of the relevant evidence or try to understand coin images or textual statements, we must imagine every possibility we can think of, before narrowing them down to the most plausible. But when we turn from trying to understand what has survived from the past and is before our eyes, to reconstructing the entirely lost reality that was behind it, we are in the world of imagination. Since the remote past is gone, we can only bring it back by imagining. We use every source of inspiration we can find, from our experience of human nature, or analogies from other times and places, elsewhere in the Roman world, or social-scientific models, to help us imagine what produced this evidence we can see. Imagination is not fantasy, however. It is not arbitrary. Historical explanation can never be ‘objective’ or simply ‘follow the evidence’, but our imagined scenarios are accountable to the evidence. We are not imagining indulgently, for the sake of it, but to think up the solution to our problem—much as the scientist must imagine new explanations of viral or cancer-cell behaviour, and cannot passively watch the evidence until it ‘speaks’.

- Finally, weigh hypotheses for their explanatory power. The best hypothesis is of course the one that best explains the evidence, with as little remainder as possible. But, the historian—like a conscientious detective—is under no obligation to produce an iron-clad result. When detectives feel compelled to find a culprit in spite of the evidence, they corrupt the judicial system and innocent people go to prison. It often happens that the evidence is simply not sufficient, in quantity or quality, to support a clear explanation. For the detective, this should become an unsolved crime, of which there are many. Historians are fortunate in that no one’s freedom turns on our investigations. When we cannot reach confidence because of insufficient evidence, which is often or even usually the case in ancient history, we remain in our default state of not knowing exactly what happened. For us, that is no great problem because history is mainly in the doing: in coming to the know the evidence and the various ways it can be explained. History is not religion. We are not required to believe things or champion conclusions.

Having compared historians with detectives in their core tasks (this is not original with me), I should clarify that of course there are also many differences between the occupations. For example, the police investigator works in the framework of laws enacted by her state, whereas the historian wants to understand what happened. The detective knows that not every killing is first-degree murder by the state’s definition, and needs to clarify what happened in relation to law. The historian does not. Again, the detective prepares a case for a prosecuting lawyer, who must present it to the court in accord with rules of evidence, which do not apply to historians. Perhaps most important, the detective considers motives and states of mind mainly in order to figure out what happened. The historian, at least one working in the humanities, studies events not as the end-point, to chronicle who went where on a given Monday, but to understand the human thoughts, motives, and intentions of people in the past, what Collingwood called the ‘inside’ of the event.

If we apply all this to the ancient Essenes, we have the rationale and the procedure for an investigation.

- A) Our problem: Who were the ancient Essenes? What were their motives and how did they live?

- B) Identify available contemporary evidence that describes Essenes, with direct or at least independent knowledge. These portraits are by Philo, Pliny, and Josephus. No material evidence known to be associated with Essenes has survived.

- C) Try to interpret each account, to understand why each author uses the Essenes as he does.

- D) Hypothesise the lost reality behind the portraits of the Essenes. At this imaginative ‘What if?’ stage, we are entitled to ask ‘What if John the Baptist, Jesus, or the sectarian scrolls from Qumran were Essene? How would that explain the evidence for the Essenes?’

- E) After weighing the various hypotheses for their explanatory power, we decide which are stronger or weaker, while always acknowledging the limitations of our knowledge.

Step C: Interpreting the First-Century Accounts of Essenes

Interpreting Philo on the Essenes

Philo (ca. 20 BCE–50 CE) was a member of the most elite group of Judaeans (= Jews) living in Alexandria, Egypt. Alexandria, second-largest city of the Roman empire, may have had a population of ca. 600,000, of Judaeans formed a large minority (ca. 150–180,000), though most Judaeans did not enjoy Alexandrian citizenship. Tensions between the citizen population and their Judaean minority simmered over a couple of centuries, occasionally breaking out in violence.

Philo belonged to the most prominent Judaean family, some branches of which enjoyed both Alexandrian and Roman citizenship. His brother Alexander was an eminent financial manager with connections to the imperial family. Alexander’s son (Philo’s nephew), Tiberius Iulius Alexander, was a star in this world, who would acquire equestrian status and become governor of Judaea and then of Egypt, possibly going on from there to command the Praetorian Guard in Rome alongside Titus. Although Philo had enough political standing to serve as the Judaean community’s emissary to Rome in 39–40 CE, he devoted much of his time to teaching and writing, mostly for fellow-Judaeans but sometimes for outsiders. In both cases, he interpreted Judaean law in keeping with common Platonic and Stoic philosophical principles. He was thus outward-looking and engaged with high literate culture, also visiting the Alexandrian theatre and athletic contexts, but unlike his nephew he remained energetically committed to Judaean law and customs. He is also well-connected with the Judaean homeland and with the Herodian royal family. He has visited Jerusalem at least once for a festival. He emphasises the centrality of Jerusalem’s temple in his exposition of the Bible, and he describes with pleasure the annual contributions to the temple from Alexandria.

Philo wrote at least three accounts of the Essenes, whom he greatly admired. Much of his writing has not survived, but his essay entitled Every Good Person is Free (75–91) includes an extended portrait of the Judaean group. Why?

This essay is one of a pair (the lost companion argued that Every Bad Person is a Slave) that argued a position we associate with Stoics. Namely, whereas people commonly think that good or bad things are around them, and happen to them, such that slavery would be the most devastating condition and freedom the best, in reality freedom and slavery are internal dispositions. Philo gives the example of a lion. He may be ‘owned’ by some wealthy Roman, but if the lion once looks the ‘owner’ in his eye, it is clear that he does not feel owned by anyone. External conditions do not determine our internal feelings or outlooks.

So Philo first grounds his proposal in abstract terms, from Greek and Judaean sources, and then suggests examples of people who recognise and practise this truth about internal freedom, not only Greek but also Persian and Indian. At this point he continues:

75. Palestine-Syria is not devoid of moral excellence either: it is home to quite a large share of the most populous ethnos of the Judaeans. Some among them, a body over 4,000 by my estimate, go by the name Essenes. This derives from hosiotēs (holiness)…because they have become devoted attendants of God, not by sacrificing animals but by considering it most important to cultivate their own minds as reverent sanctuaries. 76. These men, first, live the village life—keeping away from the cities because of the typical lawlessness of city-dwellers, knowing that those who live in close quarters are susceptible to an incurable attack of contagious disease on their souls, just as from the polluted air. …

85. First, then, no one’s house is his own, and not the common home of all. In addition to their living together in groups, they extend a welcome to fellow-enthusiasts [other Essenes] who arrive among them from other places. 86.Then, they have created one supply-room for all: shared expenses, shared clothes, shared common-mess meals. One could not find such common lodging, common regimen, and common table among others—proven in action, that is [as distinct from descriptions of Utopia].

Philo mentions another account of the Essenes at the beginning of his essay On the Contemplative Life. That work explores the life of a group called the Therapeutae in Egypt, who practice the life apart from society in contemplation. But he mentions that he has written a companion work, now lost, On the Practical Life. For that, he says, he used the Essenes as the best example of ‘philosophers’ who do not retreat to contemplation but engage the world.

Philo’s third account has also not survived in original form, but it is quoted extensively by the fourth-century Christian author Eusebius in his Preparation of the Gospel (8.11), which looks for groups that practised Christian values before Christ. These quotations overlap considerably with Every Good Person is Free, about Essenes living in a number of communities with shared property and meals, but also has some new emphases. Namely, they have a wide range of occupations, such as agriculture, animal husbandry, grazing herds, bee-keeping, and various trades—anything non-violent. They take wages from this work and give it to the community. They are found in large numbers throughout Judaea, in the larger towns and cities. Philo is impressed by the regard that even the most brutal of Judaean rulers (presumably he is thinking of King Herod and sons) show these virtuous men. Finally, he now confirms that they are exclusively male: ‘none of the Essenes takes a wife’. Essene communities continue in existence because they regularly receive new members.

Philo’s accounts of the Essenes are clearly his. He uses language characteristic of his works to accommodate them to his literary purposes. They are ‘athletes of virtue’, who are constantly preparing themselves by disciplined training for the contest of life. They know internal freedom. But we can plainly see that Philo knows of these Judaean communities, all around the region, and readily thinks of them when he wants to illustrate Judaean virtues in various contexts. They are not reclusive, but show their virtue throughout Judaea’s towns by their engagement with others. What kind of historical group would attract such attention from such a man as Philo?

Interpreting Pliny on the Essenes

Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), Gaius Plinius Secundus, was a different character from Philo in most respects. Launched into life from a wealthy equestrian family, he became a classic example of equestrian activity and accomplishment. He was trained in and practised law, but also spent considerable time in various military ranks and high-end political appointments for men of his class, ending his life as commander of the fleet at Misenum on the Bay of Naples. He died while investigating the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius and trying to rescue a friend’s family. In his spare time, Pliny wrote 102 volumes (mostly lost) on everything from grammar and rhetoric to military history. His most famous work is the 36-volume (plus introductory summary and prologue) Natural History.

In the introduction to this encyclopaedia of people, places, and the natural environment of the Roman world, Pliny says that his simple account of facts and figures is not very Greek, but Romans—who value truth over pleasant language—will appreciate it (pr. 24–28). Nevertheless, to enliven his lists of foreign words, he will pay special attention to the marvellous and the grotesque, the strange and the marvellous (1.7; 3.2). Pliny mentions Essenes precisely for this reason: when describing Judaea’s places, he pauses on the Essenes because they are amazing. This is not because of their great virtue, however. In contrast to the Judaean authors Philo and Josephus, Pliny mentions the Essenes to make fun of them. They are amazing because they abandon the vigorous life that Pliny obviously values so much, tired of life and unable to take the ‘rough and tumble’. They abandon cities, pleasures, and especially women. The amazing thing about them is that they continue to propagate themselves, not through procreation but because so many impotent men keep joining them. Pliny has a good laugh with his expected audiences.

Pliny approaches Judaea from Egypt in the west. After mentioning all kinds of place names there, he moves up the cities of the coast, then haphazardly mentions various inland sites, then focuses on the major bodies of water from north to south: Lake Genesar (Sea of Galilee), the Jordan River, and Lake Asphaltites (the Dead Sea). This geography is all tied up with political affairs. A good friend of the Flavians, Vespasian and Titus (he dedicates the work to Titus), who have recently destroyed Judaea and Jerusalem, he light-heartedly pictures the geography as a descent to ruin and death.

Pliny’s method is to work around each of the two lakes clockwise: north, east, south, and ending in the west. The Jordan River originates full of life-giving properties from its mountain source (5.71). Pliny gives it human emotions, in keeping with his Stoic-pantheistic outlook: it hesitates and meanders left and right because it doesn’t want to be consumed by the foul, stinking, lake of death that characterises Judaea, which he elsewhere calls ‘Judaea’s Lake’ (2.226; 7.65). So it first flattens out as the Sea of Galilee, giving life to the communities mentioned on each side. But then it must go to Asphaltites, the only product of which is bitumen, and on which the dead carcasses of animals float. He again surveys notable sites around it in a clockwise direction: Arabia of the famed Nomads to the east, a famous (destroyed) fortress and hot springs allegedly to the south. Then (5.73):

To the west, the Essenes—a solitary tribe and amazing beyond all others in the world—flee the shores, far enough from where they cause harm. Without any women and having renounced all sexual interest, they have no money and for company only palm branches! Their assembly is born again daily, however, from the crowds, tired of life and the reversals of fortune, that crowd there for their manner of living. So for thousands of ages—remarkable to say—a tribe is eternal into which no one is born! So fruitful for them is the reconsideration of life by others.

This is mainly what Pliny wants to say about the Essenes. The passage is filled with Latin phrases distinctive of his style, but evidently he is describing the same group as Philo, except from a very different, sarcastic perspective. Instead of admiring the Essenes, he finds them a curiosity. How very un-Roman of them, to find political, commercial, and family life so burdensome that they flee into seclusion!

This notice is valuable as independent attestation of Philo’s group. But scholars have mainly valued it for the end of the passage, when Pliny leaves his description of the Essenes and resumes his geographical survey:

Below them used to be the town of En Gedi (infra hos Engada oppidum fuit), second only to Jerusalem in fertility and groves of palm trees, though now likewise a ruin. After that (inde) is Masada, a fortress on a crag—for its part, not at all far from Asphaltites. This is Judaea.

This description presents no surprises. Although Pliny names a large number of sites in the region, he does not suggest that Essenes occupied a particular ‘Essene-town’. On the contrary, his account implies that just as Nomads are found east of the lake in Arabia, Essenes are inland on the west side. Nomads were famous for their transient way of life, and Pliny mentions them in various places (e.g., Numidia is named after them at 5.22). On the west side, correspondingly, far from the famous lake’s foul smells—i.e., up in the Judaean hills—one finds Essenes. He contrasts Masada, which is quite close to the lake. His exaggerated humour about having only palm trees instead of women fits with Philo’s claim that Essenes avoid the moral hazards of city life. When Pliny mentions that En Gedi (ruined in the war) used to be below the Essenes, and that Masada, the last item on his agenda, marks the limit of Judaea, he is mentioning reference points familiar to his readers.

Because the interpretation of Pliny’s geographical remarks will become the main argument for connecting his Essenes with Qumran, we need to pause here to be clear about his meaning. Ancient Greek, Latin, and Hebrew authors had words available for the compass points (north, south, east, west). Although we, with a highly cultivated ‘map mentality’, often use ‘above, below’ to refer to north and south, they—lacking our maps and assumptions—used ‘above, below’ for elevation. ‘Above’ meant ‘higher than’, in the hills if the context is topographical; ‘below’ meant literally lower than’. That Pliny was understood this way in antiquity is confirmable from one of his early interpreters.

A century and a half after Pliny wrote, C. Julius Solinus decided to ransack his works for all the most interesting bits: the marvels that Pliny included to spice up his rather tiresome account of foreign places and natural processes. Without mentioning that Pliny was his source, Solinus produced his much more compact and interesting Collection of Remarkable Things. He expanded on Judaea’s very different bodies of water as a marvel in themselves, quickly changing from fresh and life-giving to dead and foul. But he skipped the clockwise tour of the lakes to include information possibly derived from Josephus (War 4.483–85) about the divine destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and the fruit that looks like an apple but turns to dust. He has noticeably dropped Pliny’s snide tone even while describing the same group (35):

The interior parts of Judaea (interiora Iudaeae), which look westward, the Essenes occupy. … No woman is there: they have altogether renounced sexual intercourse. They don’t recognise money. They subsist on data palms. No one is born there, and yet the number of men doesn’t fall short. The place itself is devoted to chastity. Many from the various nations may come there, but no one is admitted unless he pursues the virtue of chastity and innocence. … So, incredible to say, beyond the long expanse of ages, though childbirth has ended, it is an eternal tribe! The town of En Gedi used to be below the Essenes (infra Essenos fuit), though it is now utterly destroyed. But its glory endures even still, not diminished at all by time or by war, in celebrated woods and magnificent palm groves. The boundary of Judaea is the fortress of Masada (Iudaeae terminus Massada castellum).

This early paraphrase confirms important points. First, Solinus understood Pliny to locate Essenes in various places west of the Dead Sea. Second, he understands Pliny’s brief remark inde Masada not to indicate a north-south line of sites, given that Pliny has obviously approached from the east and south, but rather to mean ‘the last place to mention in Judaea’ is Masada, to close his discussion of Judaea before he (Pliny, followed by Solinus) proceeds to the Decapolis.

Before the discoveries at Qumran (from 1947), scholars understood Pliny’s description in the way that Solinus did, as a rather vague indication of settlements in the highlands above En Gedi. If anything, they needlessly focused on the heights just above En Gedi. So the historian Emil Schürer, in his famous Handbook on first-century Judaean history, had to remind colleagues that, in light of Philo’s and Josephus’ more knowledgeable location of Essenes all around Judaea: ‘we should be much mistaken if we were, according to Pliny’s description, to seek them only in the desert of Engedi on the Dead Sea’ (1901 English translation). In other words, Pliny’s broad geographical scheme is compatible with Philo’s and Josephus’ picture. After the Qumran discoveries, scholars’ interpretations of Pliny would dramatically change, and this change presents a methodological problem (below).

Interpreting Josephus on the Essenes

Although Josephus’ family was not one of the three or four families that supplied Jerusalem’s high priests, it was close to them and part of the Jerusalem establishment. This is clear in spite of his over-the-top boasting about his ancestry (Life 1–6). Born in 37 CE, he received an excellent education in both Hebrew and Greek literature, while presumably speaking Aramaic for everyday purposes. When he was just 26, the Jerusalem authorities asked him to travel to Rome, to see if he could free three fellow-priests being detained by Nero. He succeeded. The leaders must have trusted his diplomatic and communication skills. Within a couple of years of his return from Rome, they sent him north to Galilee—another sign of high standing at just 30 years of age.

Josephus’ remarkable career, including what happened in Galilee and later, is too complex to relate here and not relevant in detail for our question. The crucial point is that after the war he made his way to Rome, a free man after two years of Roman captivity, and there devoted much of the latter half of his life to writing. He produced thirty Greek volumes: seven on The Judaean War, twenty on Judaean history from Creation until the war (Antiquities), one volume of autobiography (focused on his time in Galilee), and a two-volume essay celebrating the antiquity and virtues of the Judaean people (Against Apion).

Josephus makes thirteen references to Essenes, usually with admiration or even awe. His descriptions are of three kinds: individual Essenes consulted by Hasmoneans and King Herod, most of whom are teachers in Jerusalem (War 1.78, 213; 2.567, 311; Ant. 15.373–78; 17.346; uniquely grouping Pharisees and Sadducees with Essenes to create a picture of Judaea’s three ‘philosophical schools’ comparable to Greek Stoics, Pythagoreans, and the like (War 2.119; Ant. 13.171, 298; 18.11; Life 10); and fuller descriptions of Essene life and thought (War 2.120–161; Ant. 18.18). We lack the space to work through all of these, and so will focus on what he considered his major statement: War 2.120–161. After describing a rogue Judaean teacher named Judas (calling him a “sophist” with his own school), who was active in 6 CE, he pauses the historical narrative to explain that Judaea has three traditional schools: Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes. But then he launches into an elaborate description of the Essenes alone (2.120–161), returning only at the end to dispense with Pharisees and Sadducees in a couple of sentences. The reader cannot avoid the impression that Josephus favours the Essenes, or at least that he wants to promote them before his Roman audiences.

Josephus’ tendency to pair Pharisees and Sadducees (in War 2.162–166 and Ant. 13.294, 297) and mention of Essenes by themselves, along with New Testament and rabbinic pairings of Pharisees and Sadducees but neglect of Essenes, together with Philo’s and Pliny’s discussions of Essenes but no Pharisees or Sadducees, suggests that Josephus’ ‘three-school’ scheme was not obvious but rather his artful construction to impress his audiences with a neat picture—as if someone describing British politics had said that there were three significant parties: Conservative, Labour, plus … any one of the Church, trade unions, the Lords, or Big Business. Other observers of the British scene would likely name the first two, but not the third, which is of a different kind.

Even Josephus’ main description of the Essenes is too long to quote entire, but I’ll offer first an overview and then provide some sample passages for a taste of Josephus’ tone. My main point about the overview, which may help readers envisage the passage’s content, is that Josephus really likes what scholars call ‘ring composition’. This means constructing a text, whether at a micro- or mid-level or the whole thing, in concentric circles. Modern essayists often use the same technique: begin with some observation or curiosity, move from there to the heart of your argument, then back out of it gradually until you close with a reminder of the starting point. In the ancient world, this technique was found in texts as diverse as Homeric epic, tragedy, and history (e.g., in Livy’s five-volume sections), and in part it satisfied the typically Greek concern for symmetry. But in all times and places, such techniques assist communication by reassuring readers that an author will not lose them in a jungle, but has crafted the communication in artful way: they are moving together on an excursion to an unknown centre, but will return safely to their starting point—and not be left to find their own way home.

Josephus says plainly at the beginning of Antiquities (1.7) that he composed War in such a way that the opening would match the closing, and that is in fact the case. For example, the opening lines of the narrative (1.31–32) refer to a temple built in Egypt, to which Josephus says he will return. He returns only at the end of the work (7.420–426). The tragic story builds up toward a pivotal passage in the middle of the middle volume (4.305–365), where Jerusalem’s chief priests are murdered and ‘tyrants’ take over, after which everything unravels into chaos. This concentric structure is not the same as the dramatic one, which reaches is climax with the fall of Jerusalem at the end of Book 6. It is more in the vein of a tragic effect, in which all kinds of good intentions and presumed knowledge of things work toward a central moment of discovery or realisation of reality, for the work’s audiences but also for characters in the story: the scales fall from their eyes and horror begins.

These reflections on Josephus’ artistry help us to take in his portrait of the Essenes, which has a concentric structure at the medium level. Thus, it opens and closes with references with references to Pharisees and Sadducees, who are absent from the main account. At one step in from the beginning and from the end, Josephus discusses women and children, who are likewise absent from the large account between those points. At the next stop, his description of Essenes as ‘despisers’ of wealth and private property and pleasure (2.122) matches his later claim that they are despisers (same rare word) of suffering and death. Then (2.123) he speaks of their choice of leaders, a topic he returns to on the way back at 2.150. Still heading toward the centre, he portrays their piety, which treats the Sun as God and prays each morning for him to rise (2.128), while on the way back he describes their way of covering up while defecating into holes that each man digs, so as not to offend God’s rays (2.148). Finally we reach the centre, which is clearly signposted by two rare Greek compounds: how people are ‘reckoned in’ to the group (how they join) and how they are ‘reckoned out’ (kicked out). And in between these two flag posts are twelve oaths that initiates must take, which summarise the whole of Essene piety.

Notice that the first two—to observe piety toward the deity and justice toward humanity—are Josephus’ own most characteristic pair of virtues, which he uses to characterise everyone from Israelite kings to Judaean rebels (who fail on both counts) and John the Baptist (who embodies both). Like Philo and Pliny, he has clearly made the Essenes his own and accommodated them to his literary purposes. This becomes clear in a comparison of his Essenes here with his discussion of general Judaean virtues in Apion (e.g., 2.145–146, 293–294), which are strikingly similar to those of the Essenes. In particular, he repeatedly calls Essenes a tagma, the word he uses otherwise mainly for a Roman legion. They are tough men, who laugh at death and agony, just as all Judaeans do—one of the primary themes of his Judaean War. But Josephus’ distinctive use of the Essenes does not mean that they look very different from Philo’s or Pliny’s group. Here are representative passages:

120 These men shun the pleasures as a vice. They consider self-control and not succumbing to the passions a virtue. Although they have contempt for marriage, adopting the children of others while they are still malleable enough for the lessons, they regard them as family and instill in them their principles of character: 121 without doing away with marriage or the succession resulting from it, they nevertheless protect themselves from the wanton ways of women, having been persuaded that none of them preserves her faithfulness to one man. 122 Despisers of wealth: Their communal stock is astonishing. One cannot find a person among them who has more in terms of possessions. … The assets of each one have been mixed in together … to create one fund for all. 123 They consider olive oil [widely used in the Roman world for cleaning and cosmetic purposes] a stain, and … make it a point of honour to remain hard and dry, and to wear white always…

124 No one city is theirs, but they settle amply in each. And for those school-members who arrive from elsewhere, all that the community has is laid out for them … and they go in and stay with them… as if they were the most intimate friends. 125 For this reason they make trips without carrying any baggage at all—though armed on account of the bandits. In each city a steward of the order appointed specially for the visitors is designated quartermaster for clothing and the other amenities.

126 Dress and deportment of body: … They replace neither clothes nor footwear until the old set is ripped all over or worn through with age. …

128 Toward the deity they are uniquely pious. Before the sun rises, they utter nothing about earthly things but only certain ancestral prayers to him, as if begging him to come up. 129 After this, they are dismissed by the curators to the various crafts that they have each become expert in. After they have worked strenuously until the fifth hour they are again assembled in one area, where they belt on linen covers and wash their bodies in frigid water. …Now pure, they approach the dining room as if it were a sacred precinct. … 131 The priest offers a prayer before the food, and … when he has had his breakfast he offers another concluding prayer. … At that, …they apply themselves to their labours again until evening. …

137 To those who are eager for their school, the entry-way is not a direct one, but they prescribe a regimen for the person who remains outside for a year, giving him a little hatchet as well as the aforementioned waist-covering and white clothing. 138 … After this demonstration of endurance, the character is tested for two further years, and after he has thus been shown worthy he is reckoned into the group. 139 Before he may touch the communal food, however, he swears dreadful oaths to them: first, that he will observe piety toward the deity; then, that he will maintain just actions toward humanity; … 140 that he will always maintain faithfulness to all, especially to those in charge, … that he will neither conceal anything from the school-members nor disclose anything of theirs to others, even if one should apply force to the point of death. 142 In addition to these, he swears that he will impart the precepts to no one otherwise than as he received them, that he will keep away from banditry, and that he will preserve intact their school’s books and the names of the angels. With such oaths as these they secure those who join them. ..

147 They guard against spitting into [their?] middles or to the right side and, even more than all other Judaeans, against applying themselves to labours on the seventh days: for not only do they prepare their own food one day before, so that they might not kindle a fire on that day, but they do not even dare to transport a container—or go to the toilet.

148 On the other days they dig a hole of a foot’s depth with a trowel—this is what that small hatchet given by them to the neophytes is for—and wrapping their cloak around them completely, so as not to outrage the rays of God, they relieve themselves into it [the hole]. 149 After that, they haul back the excavated earth into the hole. (When they do this, they select the more deserted spots.) Even though the secretion of excrement is certainly a natural function, it is customary to wash themselves off after it as if they have become polluted….

Despisers of terrors, triumphing over agonies by their wills, considering death—if it arrives with glory—better than deathlessness. 152 The war against the Romans proved their souls in every way: during it, while being twisted and also bent, burned and also broken, and passing through all the torture-chamber instruments, with the aim that they might defame the lawgiver or eat something not customary, they did not put up with suffering either one: not once gratifying their tormenters or crying. 153 But smiling in their agonies and making fun of those who were administering the tortures, they would cheerfully dismiss their souls, [knowing] that they would get them back again. 154 For the view has become tenaciously held among them that whereas our bodies are perishable and their matter impermanent, our souls endure forever, deathless: they get entangled, having emanated from the most refined ether, as if drawn down by a certain charm into the prisons that are bodies. 155 But when they are released from the restraints of the flesh, as if freed from a long period of slavery, then they rejoice and are carried upwards in suspension. … 158 These matters, then, the Essenes theologise with respect to the soul, laying down an irresistible bait for those who have once tasted of their wisdom.

Step D: Imagining Hypotheses

Preliminary Results

We have completed the first four of our five steps: (1) posing the historical problem of characterising the Essenes of Roman Judaea; (2) identifying the contemporary sources that describe Essenes; (3) trying to understand, in a preliminary way, each of those sources (how the Essenes fit in each writer’s work); and now (4) imagining hypotheses about the real Essenes that would explain all of this evidence.

It seems to me not very difficult to imagine a historical group that would account for these diverse portraits, because they agree on so much: groups of celibate males widely dispersed in Judaea, who work at trades and agriculture but pool their incomes to exclude private wealth, and who eat and live together in communities. They avoid the swearing of oaths, at least in ordinary affairs, and do not keep slaves. Highly disciplined and rejecting all such common values, aspirations, and fears, they study sacred texts, especially on sabbaths. But they are not contemplatives. They live in society, often travel from one community of brothers to another, and they are well known to Judaea’s rulers, who accord them respect. When such pillars of the Judaean establishment as Philo and Josephus look for the purest examples of Judaean values, they independently and readily choose the Essenes, describing them at length and in glowing terms. Pliny does not disagree on any substantial point, but he (followed by Solinus) includes them as source of entertainment in his derogatory portrait of the Judaea recently destroyed by his friends, the Flavians.

Now two related points of method. First, we would not expect independent authors to focus on the same things or use the same language. And that is what we find. Each writer’s diction (Philo: freedom, athletes of virtue; Pliny: marvels, incredible; Josephus, piety and justice, despisers of pleasures and death) fits his account, accommodating the Essenes to his themes. But we can easily discern the same group behind the various descriptions, especially where the independent accounts intersect.

Second, features found in only one account cannot attract the same confidence as those that have multiple attestation. Historians, like detectives, prefer corroboration. Josephus’ afterthought (War 2.160–161) about a group of Essenes that marry, solely to produce children (not from love or intimacy), but in all other respects follow the strict Essene practice he has described at length, conflicts with the plain statements in the other accounts and with his own later claim that Essenes do not marry (Ant. 18.21). It is also difficult to imagine in real life couples with children following the regimen he has described. So we must suspect that he had some reason for imagining such a group in War 2. With other issues, which are not contradicted but also not confirmed (Philo’s bee-keeping and grazing, Josephus’ sun-worship, three-year initiation, toilet practices, adopting others’ children), we must simply say that they are possible but we cannot confidently ascribe them to the real Essenes.

In saying that only these three first-century authors describe Essenes, I have deliberately not included a marginal case, but will mention it now. Early in the fifth century, the Christian bishop Synesius of Cyrene wrote a biography of the political orator Dio of Prusa (ca. 40–120 CE). Dio ran afoul of the emperor Domitian, who expelled him from Rome, but came to enjoy good relations with Nerva and Trajan. He was a member of the empire’s political elite and well-connected. About eighty of Dio’s speeches survive, along with a few letters, and Essenes do not appear in them. But Synesius claims, after praising Dio’s Euboean discourse as the key to a happy life, continues by saying (3.2):

He also somewhere praises the Essenes, a whole happy polis beyond [or alongside] the Dead Water, in Palestine’s inland, lying somewhere near Sodom itself. For that man, from the time that he began to study philosophy and gave himself over to challenging humanity, did not produce even one unprofitable speech. …

The passage presents well-known problems. It might seem to imply that Dio mentioned the Essenes in the Euboean, but he did not, and Synesius does not (cannot?) be more specific. Some scholars have held that the line about Essenes is an interpolation into Synesius’ work by someone who knew Philo, Josephus, and/or Pliny. We cannot know. In any case, even if Synesius knew that Dio ‘somewhere’ expressed praise of the Essenes, that is all that he need have taken from Dio. The rest of the description (Dead Water, interest in Sodom) sounds more like Christian writing of the fifth century, added by Synesius from what he thinks he knows. So it would be wise not to place any weight on this second-hand reference to Dio, though if the famous statesman did ‘praise the Essenes’, that would confirm their appeal for philosophically inclined elites.

Other Hypotheses: Essenes and Qumran, John the Baptist, Jesus, Christians

While we are in stages D and E of our historical investigation, imagining hypotheses about the real Essenes that would explain all the evidence (as above) and weighing such hypotheses, we cannot ignore the fact that many accomplished scholars are convinced that the residents of the site known as Qumran, on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea, and some of the scrolls found in caves near that site, are Essene. Fewer scholars believe that John the Baptist, Jesus, and/or some early Christian groups were Essene. These current proposals have taken over from pre-Qumran speculations, from at least the eighteenth century, about the Essenes as as a marginal Jewish community open to Persian, Greek (e.g., Pythagorean), and Buddhist emphases from the east.

Let me say immediately that any of these connections is possible. The discipline of history begins from the reality that we know nothing much of what happened long ago, and so need to investigate what we can. If we had a good deal more surviving evidence, it might be that only some such connection would explain it. As it is, however, the test of any hypothesis of connection between the Essenes and some other X must be this: Would it help to explain the Essene descriptions more than it would hurt? Recall: the best hypothesis about any person or group’s outlook, aims, and character is the one that explains the evidence most adequately without presenting problems. We already have a hypothetical working picture of the Essenes: If they were like the group we’ve seen above, that would explain why Philo, Pliny, and Josephus thought to use them in their works as they did.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with positing that John the Baptist was an Essene, but how would that help us understand either the descriptions of John (in the gospels and Josephus) or the descriptions of Essenes? Whereas the Essene descriptions all point to a strong communal emphasis—living together under the group’s authority and sharing the proceeds of labour is the point—John appears everywhere as a singular charismatic preacher with his own large following. How would the hypothesis that he was an Essene help us understand any evidence? The same thought process holds for other proposed connections. None is impossible, but what would they explain? If they mainly create problems, in spite of some similarities, why would we find them compelling?

This is not the place for even a half-decent account of the Qumran discoveries and their various interpretations. Very briefly, a few scrolls from caves near the long-known site of Qumran, close by the ancient shoreline of the Dead Sea, came to light in the late 1940s. The scholars who first studied them speculated, on the basis of some parallels with the famous Essene descriptions. Shortly thereafter, a priest-scholar who lived in a religious community in East Jerusalem (then in Jordan) led the excavation of the residential site. Very quickly a near-consensus formed that the site was the heart of the Essene religious community, which had also produced the scrolls that were gradually being discovered in 11 of about 60 caves nearby: some immediately south of the residential site, some up to 2.5 km to the north. This was very much the standard view, which I learned as more or less a proven fact in the 1980s.

Since the 1990s, however, this neat ‘Qumran site || scrolls from the caves || Essene descriptions’ triangle has been pulled from each corner. But the main debates have been about the residential site and its relationship to the caves. For example, the original excavators thought the site could host about 200 residents, including a lost upper storey and accommodation in some caves. But the area inside the walls, which is largely devoted substantial pools, has since been estimated to hold as few as 12, perhaps 20; some say 50 at the absolute limit. Some scholars imagine the residents as wealthy traders connected with Jericho, some as engaged in industry (processing dates or bitumen) or manufacture (pottery).

As for the scrolls, more than 40,000 fragments have been found, some so small that they have only bits of a word or two. Scholarly patience in puzzling them together has resulted in the estimate that they come from nearly 1,000 texts. Of these, roughly 40% are known biblical texts, 30% are otherwise known Judaean texts (e.g., 1 Enoch, Jubilees), and the remaining 30% or so are copies (often multiple) of previously unknown works. One partial text had been known since the early twentieth century from the storage room of a Cairo synagogue, and turned up in Cave 4 at Qumran (Damascus Covenant). Whereas until the 1990s it was common to view that third group of texts as largely Essene, reflecting the life of an Essene community in residence at Qumran, the new interpretations of the site have tended to see the caves as safe-deposit sites that may not be connected with the residential area at all. Even those scholars who continue to view the site as the home of an Essene community have usually qualified the old view on my ways: perhaps it is just one Essene outpost, and perhaps only a few of the Scrolls are Essene products or copies, the others left by refugees from Jerusalem.

I am no expert in either the Qumran site or the scrolls, which are the research focus of many scholars, conferences, journals, and book series. For our purposes here, the question is fairly straightforward: Would the hypothesis that the ‘sectarian scrolls’ are Essene and/or that Qumran was a notable Essene site help us to understand the descriptions of Essenes? Lacking any grounds for rejecting the Qumran-Essene connection out of hand, I see no reason to accept it at this point, simply because it would not help me understand the descriptions in Philo, Pliny, or Josephus. On the contrary, it would create many problems and conflicts, which do not exist if we don’t posit the connection.

Although I’m not expert in the scrolls, I have read many of the sectarian texts a number of times, partly in the original Hebrew (part of my training and in preparation for teaching and seminars), as well as a number of the standard introductions to them. These texts share a number of general features. Whether or not one calls them ‘apocalyptic’ (depending on the definition of that term), they certainly convey the sense of a righteous-remnant community, in some tension with both the priestly leadership in Jerusalem and foreigners (the Kittim), which believes itself to be living near the end of time. They have a ‘dualistic’ frame of mind, seeing life as a struggle between God and dark powers for human devotion. The mass of Judaeans, those who run the temple, and probably the Pharisees, are too lax in their interpretation of Moses’ laws and purity requirements, the last group even ‘seeking smooth things’ to get around the laws.

Step E: Weighing Hypotheses for Explanatory Power

One might immediately wonder how, if such groups were the real Essenes, men such as Philo and Josephus, as much a part of the Judaean establishment as one can imagine and quite at home in Graeco-Roman culture, would have turned to these groups to illustrate Judaean virtues. The case for identifying the scrolls as Essene has rested on two main foundations: one-for-one correspondences between the ‘community rules’ from Qumran and those that Josephus, in particular, describes for Essenes, and a new reading of Pliny’s description, such that he allegedly located Essenes … at or very near Qumran! I can take up each of these points only briefly.

The perceived correspondences are mainly between Josephus’ War 2 description of Essene life and a couple of columns in the text known as The Community Rule (1QS) from Qumran. In my view, the prescriptions do not overlap much, or distinctively, and anyway they have a different focus. Here are some prescriptions from 1QS 7.1 (trans. M. O. Wise, M. G. Abegg, E. M. Cook):

Whoever nurses a grudge against his companion … is to be punished by reduced rations for six months <one year. > Whoever speaks foolishness: three months. Anyone interrupting his companion while in session: ten days. Anyone who lies down and sleeps in a session of the general membership: thirty days. The same applies to the man who leaves a session of the general membership without permission and without a good excuse three times in a single session. … Anyone who walks about naked in the presence of a comrade, unless he be sick, is to be punished by reduced rations for six months. A man who spits into the midst of a session of the general membership is to be punished by reduced rations for thirty days. … Anyone who bursts into foolish horse laughter is to be punished by reduced rations for thirty days.

For most of this there is nothing comparable in Josephus. The Jerusalem priest does not describe such rules for Essene meetings or penalties for misconduct. But scholars quickly noticed one item that was superficially similar. Josephus does say that, among their strict observances—avoiding oaths and being very careful about sabbath observance (not even relieving themselves on that day)—Essenes avoid ‘spitting into middles or to the right side’. For scholars rather desperately looking for parallels, this one appeared to jump out as nearly decisive proof: they both prohibit spitting! How strange is that, if they are not the same group?

This parade example of alleged agreements between Josephus’ Essenes and the scrolls may serve to illustrate the general problem. First, the prohibition of spitting in groups is not uncommon. It is a source of ‘core disgust’ (along with other expulsions of bodily fluids and gases). Several gyms I have belonged to have had signs in the shower area saying ‘No spitting!’ These were not Essene gyms, as far as I know.

But second, it seems that Josephus is not talking about group behaviour as 1QS 7 is. Think about this for a moment. He says they prohibit spitting into middles and to the right side. That implies that spitting to the left is permitted, but that would make no sense at all in a meeting. ‘Hey, why are you spitting on me? You’re on my left. You can spit on Bob over there, and I can spit on you, but you can’t spit on me….’ This is silly. Although it is possible that Josephus’ Greek expression ‘into middles’ by itself would mean ‘into the middle of meetings’, his context precludes that meaning: no meetings are in view, and the prohibition is about middles and right sides. What, then, does he mean?

In the ancient world, spitting in general but especially into one’s own torso and to the right side (e.g. into a right shoe) was a ritual to ensure good luck or prevent or cure illness—a common superstitious practice (e.g., Theophrastus, Char. 16.14; Theocritus, Idyll. 20.11; Tibullus 1.2.96; Pliny, Nat. 24.172; 28.38; 38.35–39; cf. Petronius, 74.13). It is easier to understand Josephus’ Essenes as forbidding such practices—they make their own, serious investigations into curative substances and the properties of stones—than allowing left-side spitting in group meetings.

Finally, back to Pliny. We have seen that before the Qumran discoveries, his location of the Essenes in the Judaean hills, below which was En Gedi on the lakeshore, seemed to match Philo’s and Josephus’ distribution of Essenes in communities throughout Judaea, though some scholars become too focused on the area just above En Gedi. Eliezer Sukenik, who first proposed the Essene identification of the earliest scrolls to appear, was so sure of the standard reading that he thought Cave 1 near Qumran merely a deposit site for scrolls from the southwest, not that the Qumran site was Essene (Megillot Genuzot I, 1948).

But then something strange happened. André Dupont-Sommer, just when the excavation of the Qumran site was beginning, proposed a new way of reading Pliny in light of Qumran (The Dead Sea Scrolls 1952, 86 n. 1; translation of Aperçus préliminaires, 1950, 106 n. 3):

It is generally admitted that the Essene colony described by Pliny was situated near the spring of Engedi, towards the centre of the western shore of the Dead Sea; … the text of Pliny continues thus: “Below them (infra hos) was the town of Engada.” . . . But I believe this means not that the Essenes lived in the mountains just above the famous spring, but that this was a little distance from their settlement, towards the south. . . . If Pliny’s text is to be understood in this way, the Essene “city” would be found towards the north of the western shore; that is to say, precisely in the region of ‘Ain-Feshka [near Qumran] itself. Should this explanation not be acceptable, it could be supposed that the Essenes possessed monasteries other than that mentioned by Pliny and Dio in the same Wilderness of Judaea.

Notice three things here. First, Dupont-Sommer is well aware of the standard reading and understands that it makes sense of Pliny’s language. He believes, however, that En Gedi’s location ‘below’ the Essenes means ‘south of’, which would arguably place Essenes at or near Qumran. Second, he imagines (even using quotation marks) that Pliny identified a ‘city’ or settlement of Essenes, though we have seen that he does not. Third, however, he is realistic about the chances that this proposal—hidden in a footnote—will be accepted. It is a gamble, and if others cannot accept it he thinks that it would be no great loss to accept simply that Essenes were in many sites in the Judaean hills, of which Qumran was one—though this would not explain Pliny’s point that they kept a good distance from the lake, in contrast to Masada, which was close.

As long as Dupont-Sommer framed it this way, there was no logical problem. He believed that the Essene scrolls and site were Essene (because of perceived correspondences) and simply proposed that Pliny actually had Qumran in mind, but this had not been realised before the discoveries. In 1957, the famous archaeologist Yigael Yadin accepted ‘what Dupont-Sommer suggests with justice’, and by 1959 Dupont-Sommer himself could reflect with satisfaction: ‘I first suggested this new explanation of the words infra hos in Pliny’s account in 1950 … and it is now accepted by most authors’ (Les écrits Esséniens, 49).

As long as the argument remained in that form—we think Qumran and its scrolls were Essene, and if they are then perhaps Pliny had heard of Qumran and simply didn’t express himself clearly by placing En Gedi infra the Essenes—the only challenge one could bring was whether it really explained Pliny’s language, which would have been understood to refer to elevation and not compass directions (cf. Solinus). A significant logical problem arose, however, when scholars took a giant step farther. Seeming to forget that Dupont-Sommer had made this suggestion, tentatively, because of the Qumran finds, they began to persuade themselves that this was the only possible reading of Pliny, and that therefore Pliny’s description of the Essenes by itself put them at Qumran. Therefore, Pliny’s alleged location of Essenes at Qumran became an independent supporting pillar of the Qumran-Essene hypothesis. and to shore up this perception of Pliny’s meaning, they began to believe—as I was taught in university—that Pliny described an itinerary heading south down the Jordan River: Jericho, the Essenes, En Gedi, then Masada. Where else but Qumran would fit that spot for Essenes?

As we have seen, Pliny does not do this. Rather, he follows the Jordan to the Dead Sea and first describes what lies east (Arabia and Nomads), then south (two towns, misplaced), and then west (where the Essenes are, below them En Gedi). He goes around this lake, as around the Sea of Galilee before, in a clockwise direction. Notice Pliny’s use of compass directions when (not ‘above’ and ‘below’) when that is what he means. There is no line from Jericho to Masada. But in major textbooks and handbooks, one finds such statements as these. The 1970s revision of Schürer, which in its original form had chided scholars for placing Pliny’s Essenes only west of En Gedi, as Philo and Josephus located them throughout Judaea, now insisted perplexingly: ‘Hence the Essene settlement lies south of Jericho and north of En-gedi and the only location fitting this description [allegedly by Pliny] is Qumran’ (2.563 n. 6). What does Jericho have to do with it? All of the italicised emphasis in these quotations is mine.

But a new orthodoxy was born from this combination of misreading and circularity. A 2002 survey article on Qumran scholarship relates: ‘This [Qumran-Essene] identification tallies with Pliny the Elder’s placement of a celibate community of Essenes between Jericho and En Gedi south of them’. An author of major reference books on ancient Judaea was increasingly insistent. In 1992: ‘The approximate location of the Essenes’ habitation is made clear by Pliny’s geographical description. Although the term “below” may be ambiguous, the sequence of listing is from north to south.’ Hence, ‘The statement of Pliny regarding the location of the Essene community seems incompatible with any interpretation other than Qumran and perhaps one or two other sites on the northwest shore.’ ‘Then in 2000: ‘The statement of Pliny the Elder … indicates only one settlement: on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea’.

As we have seen, however, Pliny indicates no settlement at all but simply considers the Essenes, up in the hills at some distance west of the Dead Sea (famous En Gedi below them), the most obvious choice to pick out for their weirdness in his description of Judaea. To insist that Pliny’s description by itself clearly places Essenes at Qumran, when in fact the Qumran re-interpretation was hesitantly proposed because of the Qumran finds, is to make a wholly circular argument: ‘We know that Qumran was an Essene site because that’s where locates Essenes, and we know that this is his meaning because of the Qumran discoveries, which we already believe to be Essene.’

The most remarkable turn in scholarship is one I can’t deal with in terms of historical method. A considerable number of scholars, who did not work chiefly with Philo, Pliny, or Josephus, became so convinced that Qumraners were Essenes—by what struck them as definitive parallels and their reading of Pliny—that they declared the scrolls ‘primary evidence’ for the Essenes and all the accounts that actually mention and love Essenes ‘secondary’. Not only that, but they proposed that Philo and Josephus—in spite of Josephus’ intimate knowledge of Judaea and claim to have studied Essene ways (Life 10) and Philo’s claim to authoritative knowledge of a place he had visited—borrowed their material from some Greek sources that did not really understand the group at all. I can only mention this approach, leaving readers to track it down if they wish (in major studies of ancient Judaism and Josephus’ Essene portrayals). As far as I can see, it inverts historical method and leaves us without any falsifiable arguments: anything can be anything by this procedure. I could declare that John the Baptist was the truest Essene who ever lived, or that Pharisees were actually Essenes, and those who wrote about Essenes did not know what they were talking about. Again, it is always possible that John or Qumraners or Jesus were Essenes. Historical method requires imagination of all possibilities, indeed, but that must be followed by an explanation of how a given hypothesis would explain the evidence.

In the case of the Essenes, we are in the truly rare position of having three independent and contemporary authors’ perspectives on the group. In historical terms, that material should be gold. It would be strange indeed to throw it aside because of our strong conviction that some sources that do not mention Essenes and that conflict with the portraits of Essenes at numerous points, and which would not explain why men such as Philo and Josephus esteemed them so highly, represents real Essenes. That may be, but why would we think so? I don’t know how such moves accord with any notion of historical method.

Conclusions

This essay has applied standard historical method to the question of the Essenes in Roman Judaea. Our question (A): Who were the Essenes? We identified contemporary evidence that mentions Essenes (B), namely works by Philo, Pliny, and Josephus, and then (C) tried in a preliminary way to understand each writer’s account contextually. With a basic picture of writer’s uses of the group in view, we moved (D) to imagining a picture of the real Essenes, who are lost to us and, finally (E), to weighing these hypotheses for their capacity to explain the contemporary portraits of the Essenes.

We found that it is not difficult to imagine the group underlying Philo’s, Pliny’s, and Josephus’ accounts, because they overlap significantly in spite of the authors’ different purposes. They must have been impressive communities of men, living in communes in Jerusalem and throughout Judaea’s towns, to so readily attract the admiration of the two elite Judaean authors as well as the respect of rulers such as Herod and Archelaus. Although they based their behaviour in profound respect for Moses’ laws, their virtues were of a kind that resonated throughout the Roman world: simplicity, community of goods, lack of interest in pleasures or wealth, and equanimity in the face of suffering or death. They engaged in regular occupations and trades, but handed over their wages to the community and took care of each other through life’s ups and downs, abandoning the pervasive social hierarchy the surrounding world and rejecting slavery. They may have worshiped the sun as a manifestation of God, studied the curative properties of roots and stones (so Josephus). Such an image explains all the evidence for Essenes with no significant remainder. It remains unclear whether they found new members only among mature men who joined them, as all the accounts declare or imply (in Josephus the long initiation), or whether they also adopted children and some group of Essenes was assigned to procreation (Josephus alone), claims that are awkward to imagine historically though explainable from Josephus’ literary context.

It is entirely possible that other groups or individuals were Essene, Essene-influenced, or Essene-curious: including Jesus or John the Baptist, or the people of Qumran and/or the scrolls. There is much we do not know. But the historian’s question must be: How would the hypothesis that any of these were Essene help us understand the Essene descriptions? Would it solve any problems in that evidence (if so, which ones?), or would it rather create new puzzles. As far as I can see, the latter is the case.

I conclude by stressing that the three contemporary authors who describe the Essenes make them the best-known group from first-century Judaea. We know more about them from the warm and elaborate descriptions by Philo and Josephus than we know about Pharisees, and Sadducees remain quite obscure. It is curious that scholars should feel so restless about Essenes alone, feeling the need to connect them with some other group. Why can we not leave the Essenes alone, as we do other groups and teachers such as Josephus’ teacher Bannus?